5.5.24. New York City

A few weeks ago, renowned activist and feminist thinker Silvia Federici looked out at hundreds gathered in New York City’s Performance Space and simply said “Palestine is the world.” Meaning that it is exemplary of the present conditions of racial capitalism, settler colonialism, white supremacy and heteropatriarchy.

Seventy-five years after the Nakba, European and US-based thinkers are starting to see the world from Palestine’s point of view, rather than see Palestine from the world’s point of view. To center Palestine is to center the genocide in Gaza, found “plausible” by the International Court of Justice.

Days later, Judith Butler added in Paris:

Feminism, queer mobilization, trans mobilization have to all be in solidarity with Palestine now, because we all suffer from forms of state and regulatory violence that makes our live unlivable or makes us have to fight for our lives.

Unlivable lives can be mobilized and transformed by those dreams of action and freedom that can be seen in the “dark,” that space outside the narrow purview of colonial white sight. It is not literally dark, it is a dreamspace in the sense of Walter Benjamin’s dialectical/dream image. It is far from dreamy. All around is rubble.

Rubble of Words and Images

Physical rubble, first. The 2008 Cast Lead operation created 600,000 tons of rubble in Gaza. Today, it’s estimated that there are 37 million tons of rubble that will take 14 years to remove. It’s the disposable built environment for disposable human life.

This unbuilt material infrastructure is accompanied by what John Berger called “the rubble of words” in the discourse in and about Palestine, composed of fragments of the signs that were once “truth” or “democracy” and the like. This rubble is supplemented by the endless rubble of images, from AI-generated “images”to deepfakes, drone footage, revenge porn, stereotypes, surveillance captures and everything else swirling in the borders of conscious and unconscious dreaming,

April 17 saw the coincidence of opening of the Venice Biennale with the establishment of the first Gaza solidarity encampment at Columbia University. The Biennale’s slogan is the artwork “Foreigners Everywhere” by Claire Fontaine. From an opening marked above all by protest around Gaza, let’s amend that: Palestine Everywhere.

Disasters of War

Following the George Floyd Uprising (2020), the Gaza Uprising is a global protest movement formed by sharing visual media, a Disasters of War for the Instagram era. Like Goya’s 19th century prints, the images from Gaza evoke pity and create horror.

But unlike Darnella Frazier’s bravely-taken video of Floyds’s murder, the Gaza materials have been made mostly by professionals. Ironically, Israel’s blockade of Gaza has required outside news agencies to retain “stringers” in Gaza, giving work and experience to local photojournalists and videographers, like Pulitzer prize finalist Wissam Nassar, whose Instagram has 1.7 million followers.

These are challenging materials, to say the least. Shattered bodies, dead children, starving children, apocalyptic cityscapes. Rubble of all kinds, moral, physical, political, visible. In these threads, you find reference to mass graves at Gaza hospitals, or the murder of doctors, that mainstream media skip over. The journalists know how to frame and shape their work by “international standards” so that “western” audiences find it convincing. It does so because such levels of civilian casualties are a disaster, plain and simple.

Asked to look and to draw conclusions as to whether this is war against terror or a genocide, the response from the global majority comprised by urban youth with Internet access has been an uprising.

The student activists in particular see what’s happening every day in their Instagram or Tik Tok feeds. The liberal decision makers at universities don’t see it at all, relying instead on self-censoring print media.

Persistent Looking

What has been seen from Gaza challenges the post-Black Lives Matter consensus in the US against showing distressing imagery. In November 2015, police in Chicago were forced to release the dash-cam video showing the murder of 16-year-old Laquan McDonald. So awful was it that Black Lives Matter activists called time on sharing scenes of Black suffering and death.

In 2016, Black studies scholar Christina Sharpe further called for the “redaction” of photographs like those taken of enslaved people for Louis Agassiz. That allowed viewers to focus on the resistance in Renty and Delia’s eyes.

This injunction was notably observed in January 2023 when Tyre Nichols was beaten to death by Memphis police, so that the video was not widely shared by activists and their allies.

The visual archive from Gaza since October 7th has been very different. Often appearing fleetingly on social media feeds designed to prevent downloading, it can be difficult to recover or record precisely what you have seen. As a result, the call from Gaza has been to look at these photographs and videos as far as possible, echoing Mamie Till Bradley showing the world what had happened to her son Emmett Till in 1954. This is a persistent looking, one that refuses to look away or scroll past what is happening.

Venice: Palestine Everywhere

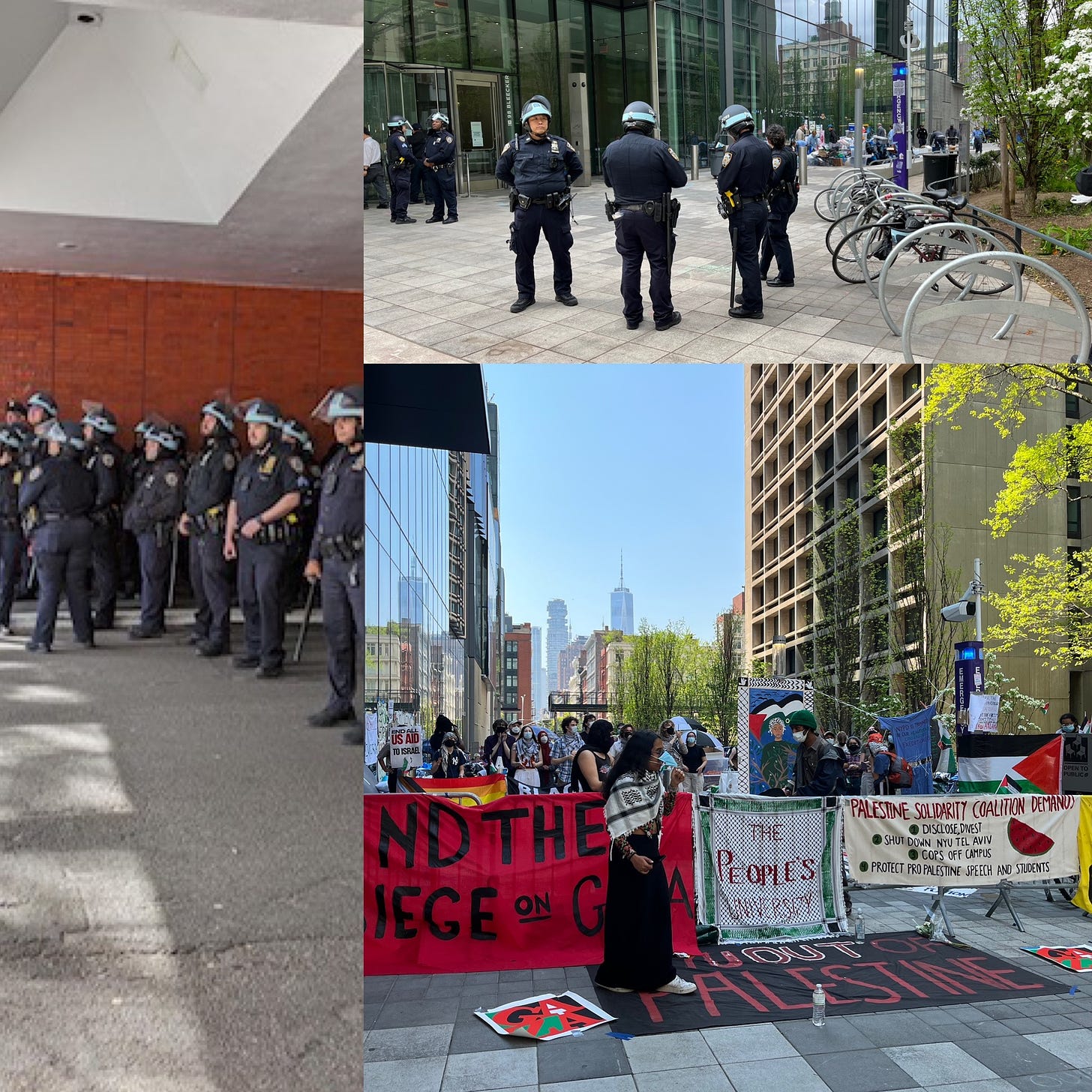

The 2024 Venice Biennale preview was dominated by protests against the occupation. On the first day, artists and others forced the Israel pavilion to close. But private tours were offered, as evidenced by the video inside playing. The very fact that Israel’s pavilion is adjacent to the US made the topography of this artworld all too clear.

Inside the Biennale space, protected by QR code entry, reinforced with required photo ID and armed police, artists who support the boycott of Israel marked their work accordingly. US Black artists and critics created a rose petal memorial, with each petal carrying the name of a woman killed in Gaza—this too attracted Italian police. The Garibaldi monument and other locations were tagged with bandanas saying “This is not a war, it’s a genocide. All the peoples of the South are Palestinians.”

The Dream of Action In the Wake

Palestinian artists themselves organized actions and exhibited off-site. The Freedom Boat docked at the entrance to the Biennale and provided a key intersection with the small boats crisis of migrants and refugees. Readings of poetry from Gaza were held each day, providing a time and space to gather and reflect. The poems were printed and given out free to those able to attend.

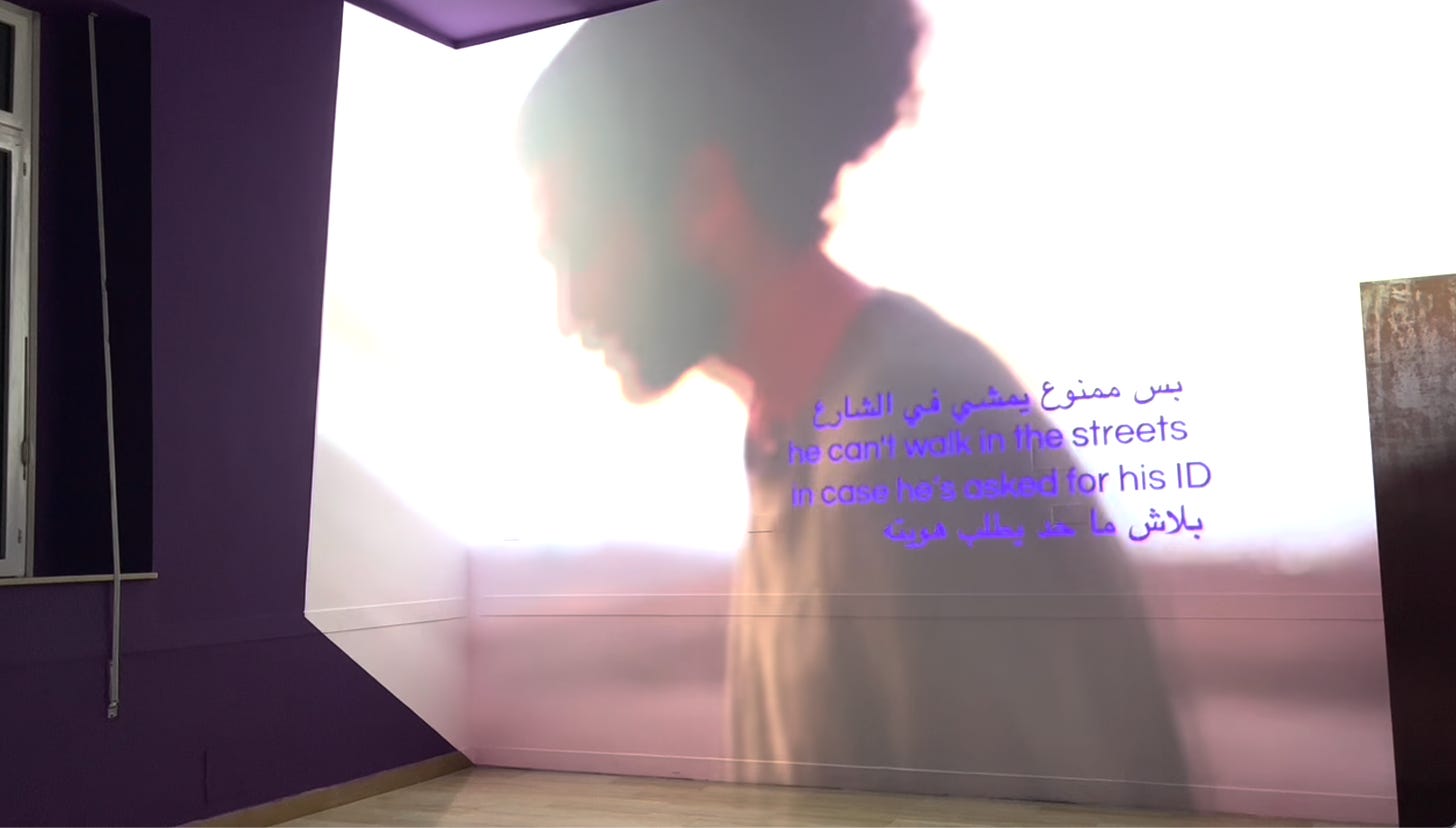

In a side alley, a small but powerful group show called “South West Bank” centered Palestine and the work of the Dar Jacir center in Bethlehem. Paesaggio Umano (2022) a video by the artists Emily Jacir and Andrea de Siena created an intriguing intersection with the films of Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme in the exhibition “Nebula.”

Paesaggio Umano was created by a series of dance and movement workshops at Dar Jacir. In one sequence, figures are seen lying on the ground. One struggles to rise, clutching her throat. As she gains her ground, others also rise, hands on throats, until they move into a collective dance that allows the final prone figure to rise. It reversed “I can’t breathe,” an embodied refusal to be expunged.

Abbas and Abou-Rahme’s film Until we became fire and fire us (2023) is a dense evocation of “disrupted lands and fragmented communities.” In one sequence, a person identified as a “fugitive to be free” in Jerusalem is seen amidst the rubble. He can’t be outside, says the text, in case IOF ask for ID. Yet he appears to be outside, so the location is imaginary or dreamed, whether sleeping or awake. The fugitive walks and creates a sequence of movement to express this paradox.

As Frantz Fanon wrote in Wretched of the Earth “the dreams of the colonial subject are…dreams of action.” These films are dreams of action in the wake. Seeing in the dark amidst the rubble of word and image is general condition of this dream of action. That the actions seen today follow the taking down of Fanon’s “world of statues” in 2020 is the expression of their decolonial structure over the past seventy-five years.

Encampments and the Dream of Action

And so, now the war comes home. The dream of action has created the wave of Gaza solidarity encampments across the US and now Europe in the wake of the genocide. The camps refuse to participate in the always “compartmentalized…hostile world” (Fanon) that sustains that genocide.

By decolonial counterpoint, the encampments are and were above all convivial, small, peaceful and hospitable. Such conviviality is always a counter to counterinsurgency, making it anathema to all forces of occupation from IOF to NYPD. In the dream of action, says Fanon, “I burst out laughing.”

Encampments from Tahrir Square to Occupy Wall Street and the liberated zones on university campuses are messy, happy, and chaotic, even as they autonomously generate learning and study. As the Center for Convivial Research shows, conviviality flows into “autonomous learning spaces,” undoing the violence of the debt-for-credit machines that the authoritarian “university” has become.

By creating known and knowable spaces of counter-counterinsurgency, encampments remap city space. On May Day, wildcat marches in New York City connected the encampments at NYU, New School, CUNY and Columbia, making a different city visible. This city does not segregate or compartmentalize, it takes the “right to the city” (Harvey) for granted.

This dream city prefigures what is needed in a world of pandemics and global heating. It shows that a city region can function as a complex of archipelagos, rather than a centralized hierarchy. It’s the grounded convivial network, rather than the top-down supertall wealth pyramid. Such a psychogeography of freedom and action shows how the region between the river and the sea could function autonomously for all those living in it.

For those whose dynamic is rage, terror, hatred and fear, such a networked city is barbarism, whether in Palestine or New York. Their “civilization,” and the fear of its replacement, requires hierarchy, dominance, strength—and therefore suffering. Conviviality must be alchemically rendered into “violence” so as to sustain the colonial world.

Supremacy

That world is above all a world of supremacy. At a post-eviction faculty picket of NYU administrators on May 3, a man carrying an Israeli flag jumped among us and repeatedly shouted “White supremacist!” He meant that the Israeli flag indicated white supremacy, making the picket subaltern. Another zionist yelled “get a job”—to a picket of full-time faculty. By aligning ourselves with Palestine, the pickets were now excluded from white and Jewish supremacy alike.

On the same day, a meme showing a Confederate flag flying above an Israeli flag began to saturate certain quarters of the Internet. Whether it’s “real” or not is beside the point: the meme sutures these two forms of supremacy, as seen in practice at the January 6 insurgency.

In the supremacist worldview, neither group sees Israelis as Jews. For white supremacists, “Jews” become Israelis by using colonial force to preserve racialized hierarchy. The resulting supremacist nationalists are therefore “white.” By the same token, Israelis lamented that October 7th made them “Jewish” again—because they were “weak” like Jews, not strong like national subjects. For such Israelis and their allies, the annihilation in Gaza has restored supremacist heteropatriarchal nationalism.

It’s Not Over

Most importantly, the war is not over. IOF have been bombing Rafah at night with minimal Western media coverage. As Patrick Wolfe famously showed, settler colonialism is a “structure not an event,” one that operates to eliminate the Indigenous. The sacking of Rafah is instrumental to that end.

College officials are relying on the end of semester to quieten things down as students head home. Perhaps that will happen, perhaps not. Either way, it’s time for those of us who are above college age to step up by creating convivial zones and a network of autonomous learning spaces to remake and remap the city as something other than a colonizing hierarchy.