Tailoring Freedom: The London Strike As A Lens

Last week I was in London and it was on strike. Some 750,000 workers from teaching to transport, hospitals and local government joined university lecturers on strike. As Argentinian feminist Verónica Gago says, “the strike is a lens.” With London shut down by a Tube strike, I wandered across the city, using this lens to “see” how its built environment frames white reality and white sight. The thoughts and images are fragments from exile, like the “way of seeing” itself, first named by Barbadian writer George Lamming in 1960.

Because Brexit prefigured Trump, it’s worth paying attention to the UK. London on strike made visible the damage finance capital has done to the possibilities of life, even as the latest bank crash unfolds and Trump calls for a second insurrection. The contactless city exists alongside a material one. Contactless is the domain for endless financial transactions behind barricades against migrants, children and fun.

The strike constitutes movement and connection, which the Swiss-Haitian artist Sasha Huber calls “tailoring freedom” in her exhibition currently on show in Shoreditch. I drifted from the British Library to this show during the strike. This is what I saw.

Permanent Verticality

Social movements are horizontal. Finance capital has become ever more aggressively vertical. Across London, fragile banks finance towers to fortify their vertical world, a clumsy visualization of their motto “the only way is up!” To adapt W.E. B. Du Bois’s definition of white ownership, in this version of white reality, stocks rise and capital increases forever and ever, amen.

Permanent verticality requires that markets always go up, while interest rates don’t. Unfortunately, according to the older neo-liberal orthodoxy still in place at central banks, unemployment must now go up to bring inflation down. It’s not working.

Higher interest rates crashed the small speculative banks like Silicon Valley Bank because clients withdrew their money and the banks didn’t have any. So 20th century for a bank to have money on hand, right? No, sorry, wrong. One major bank, Credit Suisse, has fallen. Does it stop here? Don’t bet on it.

The umpteenth time is beyond farce. As Occupy Wall Street said in 2011: “Banks got bailed out. We got sold out.” This mechanism is built-in to speculative capital’s operating system. Last week, Biden bailed out the banks and opened the Arctic for more climate catastrophe causing oil extraction as part and parcel of keeping the illusion of permanent verticality going.

From the ground during the strike, without all the usual bustle to distract your attention, it looks mad. Livable space adjacent to featureless unoccupied towers. Cranes standing guard over carefully concealed condo spaces—available for pre-purchase from the on-site office.

Even inside the pub shown above behind Old Street, the food menu only offers something called Tex-Mex burgers. Despite the old sign, the beer on offer is a toxic blend of nasty “craft” brews, alongside the undrinkable new “pale ales,” which I can only describe as being what white supremacy tastes like.

Contactless

In the Covid pandemic, every London commercial transaction went contactless. Many places display signs saying that cash is not accepted. What was once the fiction of “legal tender” is now an unwanted advance. Hand-washing would eliminate the very small risk of transferring the virus from cash. But the change is made. Even street markets now do contactless only.

About 50% of all purchases in the UK are contactless, running about 10% ahead of global trends. Contactless payment transactions involved $1.1 trillion in 2022, expected to rise rapidly to $5 trillion by 2027. That’s still a lot of money, even today.

Paper money is not something to get nostalgic about. But a system that requires you to purchase a device and pay a monthly rent just to get access to your own money is no improvement. And that’s before any financialization has been made of all the data gathered, bundled and marketed via contactless payment.

Contactless is a metaphor as well as a payment system, standing for an ever more compartmentalized and fragmented social order. Those people who cannot live contactless lives, like the refugee or the unhoused, have become subject to moral panics.

Empire’s endgame is that in order for white people to live—meaning to remain at the top of a racialized hierarchy—those bodies that evoke contact by their mere presence must be excluded.

Inhale

On strike days, different classes became visible by means of their inhalation. Younger people appeared everywhere in Lycra, running or jogging. Whether they were heading to work on foot or taking the opportunity of quieter streets to exercise during the day, the city was not much more than a backdrop.

Another group of men, mostly bearded, stood outside wearing parkas against the cold, smoking furiously. By which I mean, they were inhaling fast but also manifesting fury. One such smoker stood on a balcony, surrounded by England flags, doing everything he could to perform white sight.

Ruins and Regulations

Creating a permanently vertical contactless city creates ruins and requires regulations. Outdated satellite dishes cling to walls like ivy. There’s an occasional ruined phone box, once intended for land line calls using money—that conjuncture is gone. One building was entirely demolished except for one staircase that had been turned into a mast for cellphone receivers and transmitters. That’s the contactless city.

The new estates have gates requiring key fob entry. Once inside, the residents are subjected to a barrage of regulations: no ball games, no music, no drinking. Why don’t they just get straight to the point and say “no fun”? Everywhere in London is monitored by CCTV. People are said to be captured 300 times a day on average. But the cops are an out-of-control racist, misogynist mob: and that’s from an official report.

So effective has the erasure of all past lived experience become that the real estate people now fake it. Shiny new murals have been placed in Shoreditch side streets to give the illusion of tagging. An apparently ruined house becomes a canvas. But wait. One tag reads “George Davis Is Innocent,” a political campaign from 1975. In fresh white paint. Look a little closer and a very discreet nameplate announces that the structure houses an architectural firm in the yellow brick section.

Striking, Tailoring and the Practice of Freedom

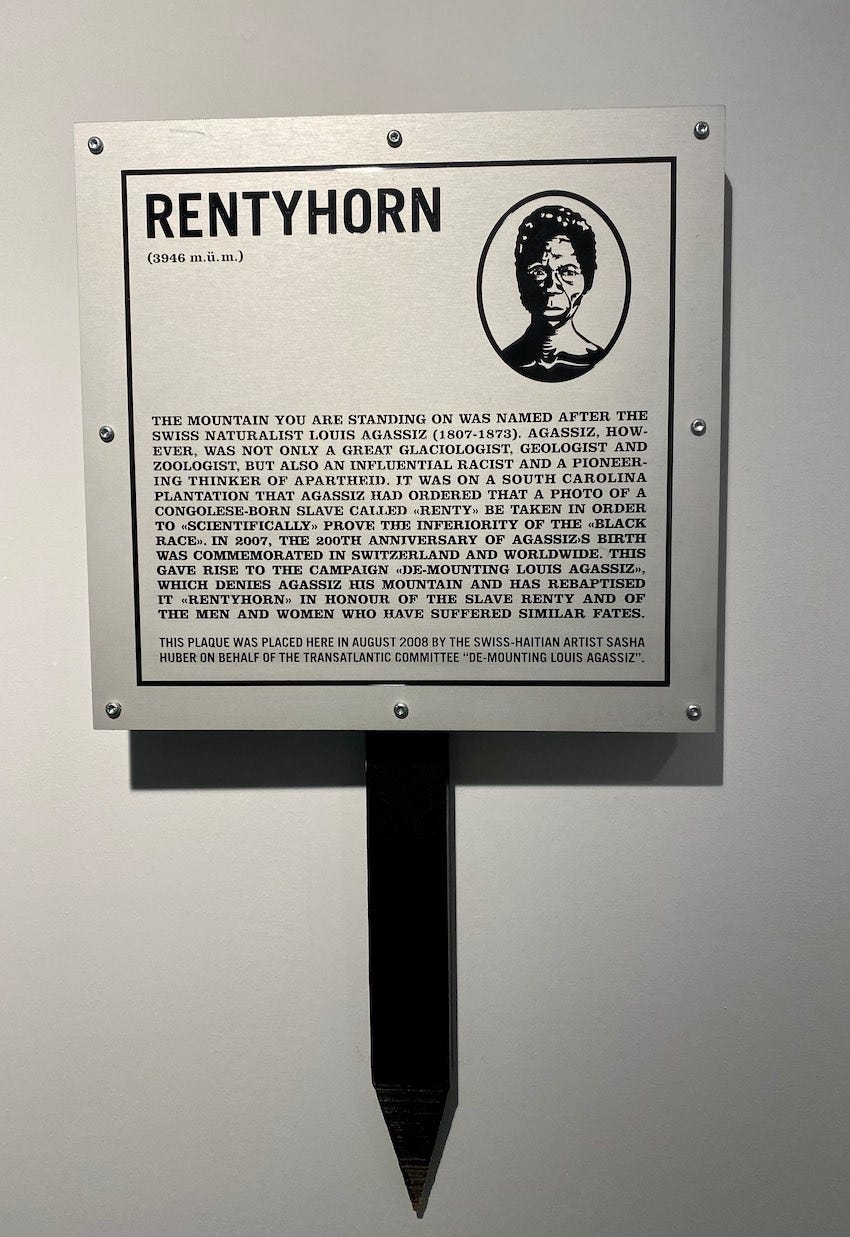

Not far away from this attempt to financialize the past was Sasha Huber’s installation at Autograph BPG. For a decade, Huber’s activist interventions have challenged the memorialization of the Swiss race “theorist” Louis Agassiz. She has made her way by helicopter to the top of a mountain called Agassizhorn and planted a sign renaming it “Rentyhorn.” Renty Taylor was one of the enslaved Africans notoriously photographed by J. T. Zealey for Agassiz in 1850.

Luminous at the heart of the space are a series in which Huber has fashioned clothing for Renty and his comrades, using metal staples. In the case of Renty and Delia, this is an active collaboration with their lineal descendant Tamara Lanier. In her own words, Huber:

dressed Renty in a suit inspired by a suit by Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), and [his daughter] Delia in a dress inspired by a dress by Harriet Tubman (1849–1913). In this work the artist used her stapling method to symbolically heal wounds while honouring the contributions of Douglass and Tubman.

These works have been widely circulated online. What you can’t see is how the light subtly plays across the metal staples, creating depth and atmosphere, against the burnt wood background. In their use of light as part of the work, these are photographs themselves but ones that perform illumination. Hung in a circular shelter, this play of light creates a sense of connection between past and present, a circuit Huber calls “tailoring freedom.”

I call Huber’s approach “revestment,” meaning the reclothing of those made naked to be photographed or looked at. “Revest” means to clothe, and I appropriate the specialized financial term “revestment,” which means “the return of a territory to the control of a monarch or other authority.” In my sense, revestment returns the control of a person’s body to them, as a counter to contactless “investment.”

By reclothing images made by Agassiz to be seen naked, Huber’s revestment restores human dignity and allows the violence done to be seen without repeating the original trauma and without taking the visual material out of circulation.

Standing in the dim afternoon light, I remembered that my great-grandfather Alick Topper was a tailor. It’s just over a mile’s walk from Autograph to 1 Back Church Lane where my grandfather Harry Topper worked as a draper’s assistant in 1911 (an apprentice to a cloth dealer), aged six. That place is long gone, turned into a railway bridge. No need to be nostalgic about child labor though.

The workplace was at the corner of Cable Street, where a barricade was built by tailors and other migrant workers in 1936 to prevent the police from opening the roads for Oswald Moseley’s fascist Blackshirts. Tailoring freedom has a long history.

Today’s strike tailors a new practice of freedom. Connecting health to transport and education as a coalition of protection against present-day contactless violence, the strike was becoming a movement. I saw this in action at a strike meeting at Goldsmith’s College, where the very length and bitterness of the dispute had visibly formed a dynamic coalition of students and staff.

Will they win? is the usual question. It’s the wrong one. By creating this dynamic movement, they’ve already won by creating contact and life in the contactless city. If the drive toward permanent growth does in fact crash the global financial economy, there will be those who are already versed in how to move in its ruins. And they will be needed against the new Blackshirts in their MAGA hats, screaming “take back control.”