The abolition of white sight is not genocide

In the first days after the publication of the book, White Sight: Visual Politics and Practices of Whiteness, a range of bots and anonymous online posts have claimed it advocates for “white genocide.” As written, that would be a genocide carried out by people identified as white. What I presume they mean is a genocide of people identified as white. What I actually wrote was “abolition.” Abolition undoes and unbuilds systems. Genocides exterminate people.

It’s not just trolling. The effort to make “abolition” mean “genocide” is part of the moral panic surrounding any effort to learn about racializing as a system of oppression. Emboldened by its legal takedown of AP Black Studies, Florida is now seeking to ban all study of gender, race and intersectionality from higher education. Similar bans can be found across the country. This week, the University of Texas system suspended all DEI initiatives.

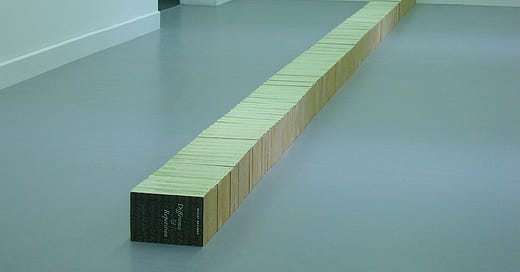

Claire Fontaine. “Lever.” (2007).

Just as Glenn Youngkin pulled off an upset win in Virginia campaigning against reading Toni Morrison, Republican candidates are in an escalating contest to see who can be most repressive. The calculation is that with Federal elections determined by a rounding error of votes across several states, aggressive white supremacy can win.

It is a small win for them that I had to write this post. But as unpleasant as the encounters can be, I think we now have to resist every instance of far-right trolling and support others when they are attacked.

As Verónica Gago argues, “fascism today focuses on disciplining indeterminacy in desires, practices and modes of life.” For this police, my own desire to make my own whiteness indeterminate— with the result that light skin would have no dominant meaning—cannot be allowed. Just as I must be a “self-hating” Jew to support Palestinian freedom, only a “genocidal” white person could want to abolish whiteness as a system.

To return to the basics, whiteness in general is not an attribute of specific bodies. It is a system of creating hierarchical difference. It has nothing to do with skin tone. In the United States, it was not until after the Second World War that Jews and Italians were considered white. Today, there is considerable prejudice against Poles and other Eastern Europeans in Britain, despite their very light skins, as being “different.” It’s the difference that matters.

White sight in particular is a set of technologies first developed as part of colonialism and frequently upgraded and updated. White sight is not how white people see. It is a learned operating system, created collectively, of what it is to make whiteness. Once learned, it feels like a reflex. But it isn’t. It’s a learned response.

Today’s white sight combines these ways of seeing into automated formats, such as facial recognition border control, the drone, or CCTV. Seeing from above, white sight both surveys land and places all life under surveillance. It is sustained by infrastructures including borders and other forms of police but also statues and museums. Using these infrastructures, white sight produces a “white reality,” taking possession of bodies and land, ordered and arranged by surveillance. Any gap between what exists and this “white reality” is closed by violence.

For, as so often in present-day far-right discourse, the accusation that abolition is violence is simply a projection of what white supremacy itself does. The abolition of this system of white sight would entail no material harm to any person whatever. It would allow for new ways of creating meaning and becoming identified to co-exist.

Rather than be a single “white” being, I myself could be of Polish, Ukrainian, and Bukharan descent, having lived half my life in England and the other half in the United States. I’m not “really from” any one of these places, but all of them in differing degrees at different moments.

For over a century, nonetheless, there has been a moral panic in the United States that any such way of becoming entails the “passing of the great race” (Madison Grant, 1916), or its “great replacement” (Renaud Camus, 2011). If Grant’s potboiler of racializing white supremacy strongly influenced government actions from eugenic sterilization of the “unfit” to exclusionary immigration policy, Camus’s tiresome tirade has provoked a parade of young white men to violence. Both are continuing and systemic operations.

The unbuilding of white sight is part of the abolition of racial capitalism. The loss involved, as Audre Lorde once put it, is that “if the master loses control…he is no longer the master.” If you cannot be “you” without being the master—outside of all consensual intimate practice—then perhaps something will have to change, yes. Will there be camps, sterilizations and wars, as in actual genocides? Of course not.

By the same token, unbuilding the infrastructures of white sight is a provisional “practice of freedom” (Ruth Wilson Gilmore), towards the abolition in which freedom is no longer an exclusionary term. That’s the horizon to which I direct this work. For now, the task is less elegant, a day-by-day blocking, deleting and refuting of electronic hate.