Since the October 7 attacks, Israel has sought Biblical vengeance, using extraordinary violence in Gaza that has awakened a growing sense that this cannot go on. Simultaneously, an intellectual and cultural conflict has rapidly unfolded from Berlin to London and New York, which may continue even after the fighting stops.

It’s already become risky to use certain words, or to wear certain colors. Jobs have been lost, exhibitions canceled. In New York, the same elite universities that recently defended the “free speech” of white supremacists have closed down student groups active in support of Palestine

It’s for this conflict that I want to offer a set of strike actions against the colonial counterinsurgency in Gaza. Building off my last post, I call these actions “strikes in the dark” because they are actions outside colonial white reality. Use them if they help. Please make them better, or create better ones.

This is not a labor strike, it’s the “most general of general strikes,” as the artist Claire Fontaine calls the “human strike.” This strike goes beyond Bartleby’s simple preference “not to,” which is also a strike, and asks: “How do we become something other than what we are?”

The first strike action is to define which “we” is being addressed. It’s the same “we” that the Civil Rights Movement addressed in its call: “we are the ones we have been waiting for.” And then that overarching intersectional alliance can be divided for specific actions.

Your Culture Is A Battleground

This is an extended and non-continuous conflict. In the US and Europe, while the Zionist mainstream are trying to delegitimize all support for Palestine, the far-right have set out to erase all questioning of colonial and racial hierarchy.

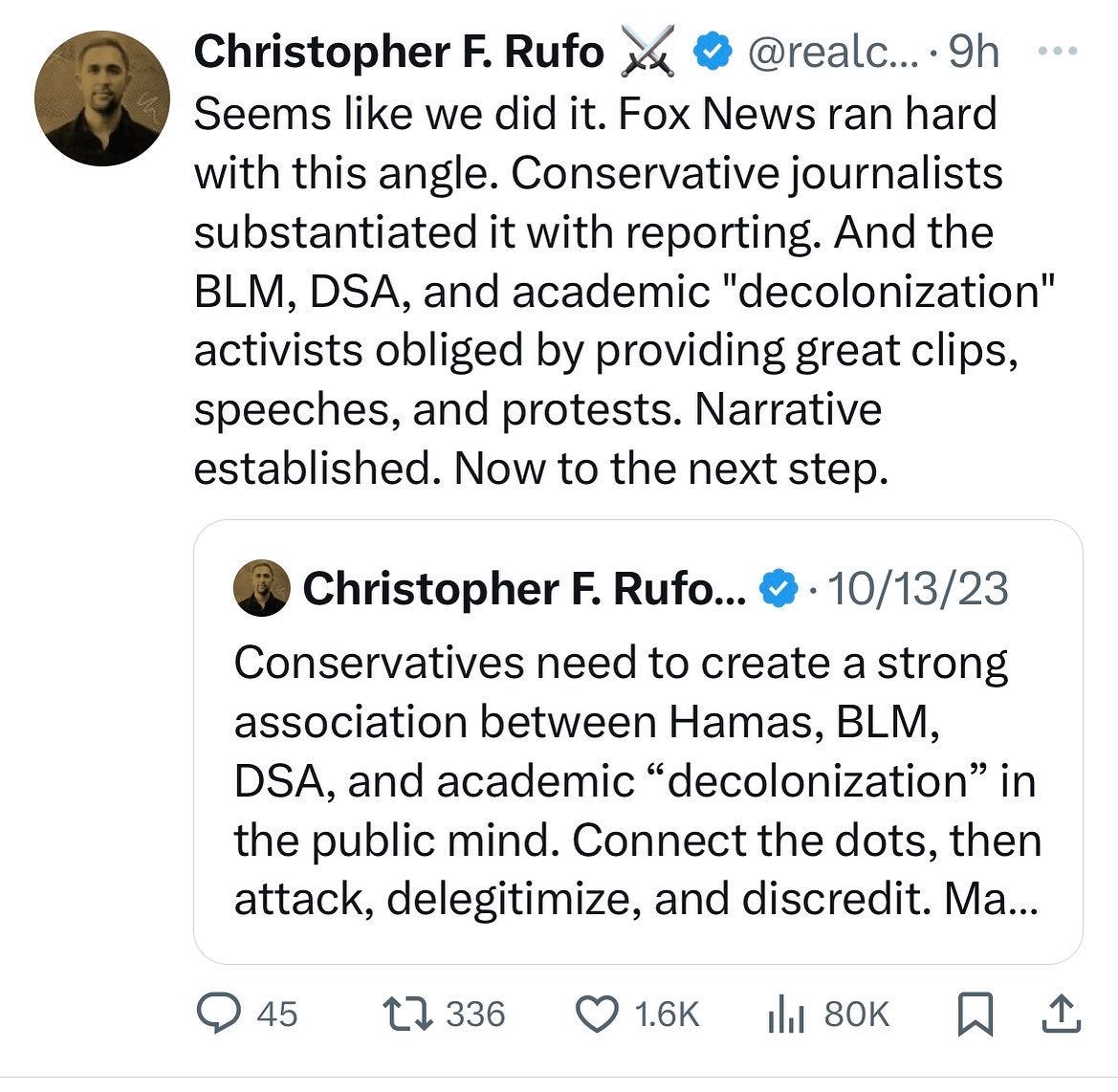

Art historian Karen Leader pointed out to me on social media that the fascist provocateur Christopher Rufo, who targeted so-called “critical race theory” to significant effect, made this connection as early as October 13 and now feels he has won—see his tweets below.

He has a case. In a front-page article on November 10, the New York Times redefined “anticolonial” in the context of Palestine as “the hothouse jargon of academia.” A month from Nazi Twitter to the Times. A day later in the Guardian, it is asserted that because some Mizrahi Jews are from North Africa, Israel cannot be a settler colony. The intellectual work at hand is to counterattack the (flimsy) foundations of these associations.

In this context, I offer three actions to strike in the dark. These actions redefine the way of seeing in mediated war; to engage with how to see in the midst of exterminationist violence; and, for those of us who are both Jewish and pro-Palestinian, how to not see ourselves as the Zionists see us.

1. Gaza is now a white sight “Kill Box”

The aerial war in Gaza is a condensed history of white sight as a colonial technology. States, the anthropologist James C. Scott famously argued, see abstractly. For the state, that is not a tree, it is a timber resource. The seeing that does this abstraction is what I call “white sight,” meaning a colonial technology that creates a white reality.

“White” here is a hierarchical relation, not a measure of skin tone. In the slave law that regulated the plantation, “whiter” persons had dominion over the enslaved. In Israel’s Jewish supremacy, Mizrahi and Sephardi Jews have dominion over all Palestinians and non-Jewish persons.

In 1648, the year in which the Treaty of Westphalia defined the modern nation-state and France expanded its colonial plantation possessions, the French engraver Abraham Bosse visualized the relation of state and seeing as the practice of armed white soldiers. Always seeing from above, this white sight erases all human and non-human life from what it surveys so that it can claim what remains as terra nullius, nothing land—or to put it another way, “a land without a people.”

US English calls the militarized possession of calculable space “real estate”— meaning white reality. No coincidence that the present-day figure head of white supremacy is a realtor.

Jump cut to 1982, the year of Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, in which a variety of new weapons were tried out, including a prototype remotely piloted vehicle, or what has become known as the drone.

Seen above in an illustration from an arms trade technical journal, the drone projects and erases a pyramidical space in front of it, just like the colonial soldier in 1648. Only now there is a screen between the soldier and where the fighting is taking place.

Drone operators, who watch the screens, call these spaces the “kill box” and there is now a US Army manual describing how to operate the kill box. It means what it says: anything that can be seen (except the small No-Fire Areas) can be killed, up to the permitted ceiling. The Army conveniently illustrate a small plane firing a missile at a piece of equipment in the middle of the box.

In its scorched-earth defense of the nation-state, the Israel Defense Force has now defined all of Gaza as a kill box. It is divided into two: the north, where everything is a target; and the south, where no-one is safe, but not everything will be shot at.

All of us who watch screens have now been trained to see like drones. Drone footage appears in all TV dramas these days, not to mention advertising, especially for cars. While the film from so-called “smart” bombs caused a sense of cultural rupture in the 1991 Gulf War, today bomb footage is treated as part of “normal” war.

Each of these sight boxes—perspectival, drone sight, or kill box—are very partial means of seeing in terms of what there is to see. Using only 50 or 60 degrees of the visual field, white sight presents this segment as as “reality.” That leaves the overwhelming majority of what there is to see as what I’m calling “the dark”—like dark matter’s relation to ordinary matter. It’s from that space, which is not literally dark, that white “reality” can be challenged.

2. In the Wake of the Holocaust

Any violence perpetrated by the Israeli state comes with a prefigured justification: the Holocaust. As it happens, I engaged with viewing the Holocaust via a close reading of the first chapter of Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake with my visual culture group last week.

In this chapter, Sharpe describes how her own class was spurred by Judith Butler referring to the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish’s book Memory for Forgetfulness, whose subtitle (not cited by Sharpe) is August, 1982, Beirut. This prose poem describes the 1982 Israeli invasion of Beirut that shattered any illusion I had as young person about Israel.

I then re-enacted Sharpe’s own teaching practice by showing excerpts of Claude Lanzmann’s Holocaust eight-hour documentary Shoah (1985), as she describes doing.

In 1985, I was a graduate student in Paris back then. Front Nationale fascists were on the streets.

In 1985, little was commonly known about the practices of the Holocaust. Then Shoah came out. Its documentation of genocidal extermination using survivor voices only was unprecedented. I saw my own reaction then again, forty years later, by showing the cleaned-up digital version to my group, a little younger than I had been: shock, silence, and surprise. To my own surprise, these young people in 2023 didn’t know the details any more than I had in 1985.

I showed the sequences identified by Sharpe that featured Simon Srebnik, one of two survivors from the extermination site at Chelmno in Poland. One opens the film with a sequence reenacting how Srebnik was forced to sing to the German executioners. When Srebnik looks out at the now quiet landscape—ignoring the memorial at his feet—he sees scenes from that past.

The later sequence doesn’t begin until almost the end of the fourth hour (3’ 55” if you want to use it), so I watched half the entire film to find it. It shows Srebnik outside the main church of the town, surrounded by Poles who remembered the Holocaust. They were glad to see Srebnik at first and filled in the details of what happened. Later they gleefully explained how what happened to the Jews was retribution for the death of Christ. The camera zooms in on Srebnik’s face, as he crosses his arms and sets his face in a thousand yard stare.

What stays with you from these descriptions is the sheer relentless elimination of Polish Jews (and later Roma people, which Lanzmann does not mention) at Chelmno by shooting and mostly by gas vans, which took fifty people at a time until 400,000 were killed.

Sharpe describes how she uses this sequence to illustrate the calamity experienced by formerly enslaved Black people in the United States after the repression of Black Reconstruction, surrounded by their former “owners” in a new hierarchy:

The means and modes of Black subjection may have changed, but the fact and structure of that subjection remain.

This powerful insight enables us, in turn, to see the Holocaust as a form of relation, intensely violent as it was, rather than as a singular moment. There are relations to Atlantic slavery, to other genocides like that of Armenia, and now to what’s happening in Palestine. This is not to say these events are the same, or that there is a scale of oppression, but there is a relation.

Looking at Shoah today is also to feel the distance between when it was made and the present. The sequences in Chelmno were shot around 1977, while the Cold War was in full flow and before the Solidarity movement in Poland had even begun. What the Poles said was antisemitic but its source was the powerful Church. In suburban London, a Catholic friend apologized to me in 1983 because she had similarly been brought up to blame Jews for Christ’s death.

Lanzmann’s interviews, reenactments, and even his camerawork were all designed, to the contrary, to make his viewers feel that they had encountered the most unique evil, an actively malevolent presence. This evil served, then as now, as a justification for Zionism. For Frantz Fanon, on the other hand, such Manichean thinking is a hallmark of colonialism.

I thought here of Hannah Arendt’s 1962 report Eichmann in Jerusalem, her study of the trial of the notorious SS operative, responsible for the deaths of yet another 400,000 people. Arendt disrupted the Manichean binary. Being “good” is often difficult, especially in times of mass violence. “Evil” is just banal—not meaningless but everyday. A functionary like Eichmann had no special qualities, he was not satanic, his head did not spin. He just went along with it all.

It is striking today how the continued insistence on Manichean evil goes together with a denial that the situation in Palestine is colonial, accompanied with the standard jeremiads against “relativism.” I am against violence, including the violence of binary simplification. If I seek to create visible relation, it is violence to call that “relativism,” if it is defined as eliminating all distinction.

Vessel

When I write like this, Zionists have a simple explanation: I am a “self-hating Jew.” It’s a strikingly antisemitic expression, if you want to go that way. White nationalists in Britain have started to accuse those wanting to acknowledge the violence of colonialism as “self-hating” too.

Learning from Christina Sharpe, I turn instead to “Note 51” in her Ordinary Notes, which is titled “Beauty is a Method.” For someone like myself, raised on the anti-aesthetic, beauty is not the most obvious turn to take. But stay with me. At the opening of this Note, Sharpe quotes a series of dictionary meanings of “vessel,” as is her wont. First comes “container” and third is “watercraft.” In between we read: “a person into whom some quality (such as grace) is infused.”

Thinking about this definition, Sharpe notes that “beauty is a practice,” one characterized by

Attentiveness whenever possible to a kind of aesthetic that escaped violence wherever possible.

At the end of my previous post about seeing in the dark, I paused on that moment where my Jewish refugee grandmother stepped off the vessel from Istanbul onto Palestine. Thinking it again with Sharpe, I remembered how often she spoke of “when I was on the boat.” The vessel. She didn’t mention disembarking—that has been my concern.

I started to think that perhaps it was the vessel that mattered. Sailing between newly Stalinist Samarkand, where Jews were no longer welcome, and the British Mandate in Palestine, where she would become a settler and a soldier, the vessel was in between, where there was, for a time, no violence. Perhaps she was indeed infused with something akin to freedom, perhaps that was “grace” for her.

I look at the photos we have of her on boats and think about that vessel of freedom. It’s a way to imagine a beginning, one that didn’t have to end the way that it did. For those of us who are often called intellectually homeless, the vessel is a place simply to be. A vessel without destination. It is not simply a “ship” because the state is a ship.

The vessel is an instrument, as Claire Fontaine put it to me in a social media conversation, to “diffuse grace, too, upon its passage, to convince and delight everyone around” (my punctuation). To be a valid Jewish person need not be framed by the diaspora/Zionist binary but can be (in) the vessel.

I’m all too aware that for descendants of the Middle Passage and other forced migrations, let alone today’s refugees crowded into small boats, the vessel has very different meanings. That teaches any “self-aware,” not “self-hating,” Jew not to claim exceptional status about their suffering.

See how this “strike” has gone from the political to the personal, from the state to the vessel. It’s worked itself into becoming a human strike. The human strike is, like all organizing, hard work.

Coda: 2048

Close to the end of his 1952 text Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon makes a surprising remark:

It is generally agreed, for example, that the Jews who settled in Israel will give birth in less than 100 years to a collective unconscious different from the one they had in 1945 in the countries from which they were expelled.

I’ve often sighed over this passage, written just four years after the Nakba. But what if that was exactly what was on his mind? In 1952, the settlers were still possessed by the phantasmagoria of colonialism. As they are in 2023. The moment of transformation is revolution not reform. It will not have been a gradual shift but there will have been a sudden moment.

What if, for all the despicable violence, or even because of the despicable violence, all of it, this is nonetheless that moment? Or the beginning of that moment. What if the sheer stupidity of the colonial war in Gaza allows the possibility to “consciousnessize the unconscious,” as Fanon put it, and stop with all this exorcism of “evil” and claims to terra nullius?

Will it have been worth it? Not at all. Nothing was worth the Nakba. One death is too many, whether in Africa, on the Middle Passage, in the plantation economy, in the extermination camp, or in Palestine.

Might it be the beginning? Let’s see.